Welcome back! I hope you found a way to carve out at least a few moments of relaxation and rejuvenation during the holiday break. Of course, the phrase “holiday break” doesn’t mean nearly the same thing for everyone, especially this time of year. For example, the folks in admissions are in the midst of working their tails off. Nowadays, the mayhem of recruiting high school students to a private liberal arts college doesn’t take a holiday, ever.

Over the last few years, we’ve learned a lot about the nature of our “competition” for prospective students. Not so long ago, many of us might have assumed that a high school senior considering Augustana College would therefore have already limited their list of potential colleges to a set of small liberal arts colleges, mostly located in the Midwest. Several decades ago this assumption was almost always correct. However, these days we know that the majority of prospective students who consider Augustana tend to look hardest at Midwestern public or larger urban private institutions as they narrow toward their final choice, not other small liberal arts colleges. This knowledge has clearly helped us make a more convincing case for choosing Augustana College, since knowing which institutions we are competing against helps us make our case more precisely and concretely.

Over the last few years, we’ve heard rumblings about other looming competitors, mostly in the form of online colleges or MOOCs (massive open online courses). Fortunately, most of those up-and-comers have blown themselves up on their own launch pads. But the underlying assumptions that justify the continued quest to build similar launch pads might be the real “competition” that we need to understand most of all.

During the holiday break I stumbled upon an opinion piece that lays bare those assumptions in a way that is as explicit as it is cocky. Neil Patel, a bigwig in the online start-up and entrepreneur world (exemplifying his marketing chops with the hyperbolic clickbait headline “My Biggest Regret in Life: Going to College”) asserts that going to college was a waste of time and money because it didn’t teach him any of the things he needed to learn in order to succeed as an entrepreneur. He argues that his college classes were little more than instances of learning isolated facts, theories, and concepts solely to regurgitate them on a test or in a paper before the end of that academic term (sort of the academic equivalent of “lather, rinse, repeat”). He argues that the entire exercise fails an ROI (return on investment) analysis because he could have learned much more useful information, grown in more substantive ways, and ultimately made more money by diving into the real world right out of high school.

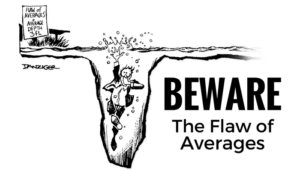

I am not sharing this article to suggest that Patel is right, although my own experience at big public universities as both a student and as an employee doesn’t do much to squash his argument. Rather, I share this article to lay bare the nature of our real competition. Because whether it is less expensive public institutions (2-year or 4-year schools), online institutions, some combination of MOOCs and competency-based education, or merely the simplification of a college choice to the largest financial aid package, in most cases our real competition isn’t other institutions. Instead, it is embedded in a series of assumptions that set up an entirely reasonable conclusion . . . IF those assumptions are, or appear to be, true. The logic stream goes something like this:

- College is primarily composed of a series of discrete experiences (AKA classes) that require regurgitating information that has been recently memorized.

- The information that is to be regurgitated exists in isolation (AKA is rarely transferable to other college experiences or to life after college).

- Accumulating completion approval (AKA at least a passing grade) for set number of classes across a set of categories earns a credential of completion (AKA a bachelor’s degree).

- Therefore, find the least expensive way to ensure a reasonable likelihood that one earns this credential.

The hardest part of facing the real world implications of this rationale is that we aren’t talking about our truth. We are talking about prospective students’ truth – the conclusions they draw as they take in what we tell them online, in print, and in person. This is the “truth” that drives real behavior. So as much as we might want to passionately argue that college transforms or that students just can’t know how what they learn will be useful until long after they’ve learned it, if the information that prospective students gather as they look at Augustana College doesn’t emphatically dispel the assumptions that undergird the logic stream spelled out above, all of our hot air (hot print, hot pixels, etc.) will likely end up sounding like a lone coyote howling at the moon.

The other hard part of facing this reality is realizing that prospective students apply this logic (fairly or not) in real time. So we help ourselves a whole lot when we show concrete evidence, from the very beginning of our interactions with each prospective student, that the experience we provide is not focused on memorizing and regurgitating information. And we help ourselves even more when we can show concrete evidence that the things students learn in one setting are directly applied during college and after college. Unfortunately, the lens through which prospective students increasingly evaluate potential colleges is not an unbiased lens. Rather, it is pre-tinted with the aforementioned assumptions, making it critical that every student sees in the most explicit and obvious ways that our understanding of a college education blows those pre-existing assumptions to bits.

All this leads to a pretty important question. If someone were to look at any of the documents or webpages that describe a given educational experience at Augustana (a syllabus, a program description, etc.), how would someone holding the assumptions described above respond? Is there a chance that the document or webpage in question would leave those assumptions unchallenged? Worse, would a review of those documents or webpages confirm those assumptions? Or would that document or webpage shatter those assumptions and open the door for a conversation about how an Augustana education might be completely different from anywhere else?

For those of us who aren’t on the front lines of recruiting students every day, this post might seem overblown. For the folks who are slogging it out in the trenches, this post might not seem urgent enough. But it seems pretty clear that these assumptions are driving the way that many prospective students and their parents start the college search process. If we don’t actively shatter those assumptions early and often, we leave ourselves susceptible to ending up on the short end of a flawed ROI argument. And to rub salt into the wound, if we end up on the losing end of this argument, we won’t even get the chance to challenge the flawed nature of their ROI analysis, because by then the prospective student has likely already crossed us off their list.

Sorry for the sobering post to start the new year. But sometimes sobering isn’t such a bad thing. In this case, we have the winning argument and the evidence to back it up. So knowing the nature of the “competition” gives us one more advantage that we ought to use every chance we get.

Make it a good day,

Mark