I’ve always been impressed by the degree to which the members of Augustana’s Board of Trustees want to understand the sometimes dizzying complexities that come with trying to nudge, guide, and redirect the motivations and behaviors of young people on the cusp of adulthood. Each board member that I talk to seems to genuinely enjoy thinking about these kinds of complicated, even convoluted, challenges and implications that they might hold for the college and our students.

This eagerness to wrestle with ambiguous, intractable problems exemplifies the intersection of two key Augustana learning outcomes that we aspire to develop in all of our students. We want our graduates to have developed incisive critical thinking skills and we want to have cultivated in them a temperament that enjoys applying those analytical skills to solve elusive problems.

Last spring Augustana completed a four-year study of one aspect of intellectual sophistication. We chose to measure the nature of our students’ growth by using a survey instrument called the Need for Cognition Scale, an instrument that assesses one’s inclination to engage in thinking about complex problems or ideas. Earlier in the fall, I presented our findings regarding our students’ growth between their initial matriculation in the fall of 2013 and their graduation in the spring of 2017 (summarized in a subsequent blog post). We found that:

- Our students developed a stronger inclination toward thinking about complex problems. The extent of our students’ growth mirrored the growth we saw in an earlier cohort of Augustana students while participating in the Wabash National Study between 2008 and 2012.

- Different types of students (defined by pre-college characteristics) grew similar amounts, although not all students started and finished with similar scores. Specifically, students with higher HS GPA or ACT/SAT scores started and finished with higher Need for Cognition scores than students with lower HS GPA or ACT/SAT scores.

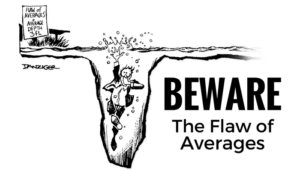

But, as with any average change-over-time score, there are lots of individual cases scattered above and below that average. In many ways, that is often where the most useful information is hidden. Because if the individuals who produce change-over-time scores above, or below, the average are similar to each other in some other ways, teasing out the nature of that similarity can help us figure out what we could do more of (or less of) to help all students grow.

At the end of our first presentation, we asked for as many hypotheses as folks could generate involving experiences that they thought might help or hamper gains on the Need of Cognition Scale. Then we went to work testing every hypothesis we could possibly test. Taylor Ashby, a student working in the IR office, did an incredible job taking on this monstrous task. After several months of pulling datasets together, constructing new variables to approximate many of the hypotheses we were given, and running all kinds of statistical analyses, we found a couple of pretty interesting discoveries that could help Augustana get even better at developing our student’s inclination or interest in thinking about complex problems or ideas.

To help us organize all of the hypotheses that folks suggested, we organized them into two categories: participation in particular structured activities (e.g., being in the choir or completing a specific major) and experiences that could occur across a range of situations (e.g., reflecting on the impact of one’s interactions across difference or talking with faculty about theories and ideas).

First, we tested all of the hypotheses about participation in particular structured activities. We found five specific activities to produce positive, statistically significant effects:

- service learning

- internships

- research with faculty

- completing multiple majors

- volunteering when it was not required (as opposed to volunteering when obligated by membership in a specific group)

In other words, students who did one or more of these five activities tended to grow more than students who did not. This turned out to be true regardless of the student’s race/ethnicity, sex, socioeconomic status, or pre-college academic preparation. Furthermore, each of these experiences produced a unique, statistically significant effect when they were all included in the same equation. This suggests the existence of a cumulative effect: students who participated in all of these activities grew more than students who only participate in some of these activities.

Second, we tested all of the hypotheses that focused on more general experiences that could occur in a variety of settings. Four experiences appeared to produce positive, statistically significant effects.

- The frequency of discussing ideas from non-major courses with faculty members outside of class.

- Knowledge among faculty in a student’s major of how to prepare students to achieve post-graduate plans.

- Faculty interest in helping students grow in more than just academic areas.

- One-on-one interactions with faculty had a positive influence on intellectual growth and interest in ideas.

In addition, we found one effect that sort of falls in between the two categories described above. Remember that having a second major appeared to produce a positive effect on the inclination to think about complex problems or ideas? Well, within that finding, Taylor discovered that students who said that faculty in their second major emphasized applying theories or concepts to practical problems or new situations “often” or “very often” grew even more than students who simply reported a second major.

So what should we make of all these findings? And equally important, how do we incorporate these findings into the way we do what we do to ensure that we use assessment data to improve?

That will be the conversation of the spring term Friday Conversation with the Assessment for Improvement Committee.

Make it a good day,

Mark